Student evaluations of teaching (SET) were originally designed to be formative by providing valuable input to instructors in higher education. When used as a tool for improving teaching, student responses to close-ended and short-answer answer questions on SETs can provide helpful feedback to instructors as well as those who mentor or otherwise work with instructors on professional development.

Since their initial introduction, however, SET have continued to shift from formative to summative. In many institutions, the ratings provide by students on a just a small subset of items far overshadow the short answers and other items that in total, provide a more comprehensive picture of college teaching. The numbers within this subset of ratings are often used in key decisions for promotion , tenure, hiring, and firing.

Using this shorter list of SET numbers is convenient and quick. Unfortunately, there is plenty of evidence that these ratings are biased and are not consistent or adequate measures of student learning (a short review of the literature can be found here). Gender bias, where female instructors consistently receive lower ratings than their male peers for the same courses or for different sections within the same course, is especially well documented. Such bias generates concern about how SET ratings are used by higher education institutions to evaluate women instructors and how these ratings impact the future morale and effectiveness of the women who read them and take them to heart.

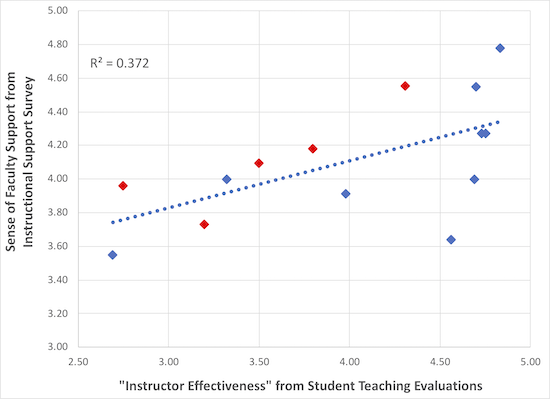

Recently, our research team compared student perceptions of how well faculty supported them in their courses with how those same students rated those faculty on student evaluations of teaching in engineering courses at one large public university. We compared a pair of median scores: Instructor Effectiveness in the Course (SET) and Students' Sense of Faculty Support (our survey).

Instructor Effectiveness was measured using the median score from one item on the university SET form: "The instructor's effectiveness in teaching the subject matter was:" Students had the option of selecting Excellent (5), Very Good (4), Good (3), Fair (2), Poor (1).

Students' Sense of Faculty Support was measured in a research-based survey that was not affiliated with the university's educational assessment office. Faculty support contained eleven items that had been validated in multiple previous studies in higher education and had a high internal consistency (reliability) of 0.92:

- The professor in this class is willing to spend time outside of class to discuss issues that are of interest and importance to me.

- The professor in this class is available when I need help.

- The professor in this class is interested in helping me learn.

- The professor in this class cares about how much I learn.

- The professor in this class treats me with respect.

- The professor has clearly explained course goals and requirements.

- The professor teaches in an organized way

- The professor often uses real-world examples or illustrations to explain difficult points.

- The professor often stays after class to answer questions.

- The professor often stops to ask questions during class.

- The professor is often funny or interesting.

All of the above items were rated on a scale from Strongly Agree (5) to Strongly Disagree (1).

When we compared SET Instructor Effectiveness to Students' Sense of Faculty Support, we found that when asked a general question about instructor effectiveness, students exhibited negative bias toward women relative to more specific (and objective) questions about faculty support behaviors. Students completed both the instructional support surveys (that contained the Faculty Support items described previously) and SET in the last 2-3 weeks of the term associated with the course being evaluated. Four of the five female instructors (80%) in the study received higher Faculty Support ratings than their SET ratings would suggest while only three of the nine (33%) of the male instructors did so (female instructors are shown in red; male instructors in blue):

Have you had a similar experience to Our Words do Matter or would you like to share a story, concern, or experience that relates to what you have just read? Click here to share (all responses are private and kept confidential). |