Women in Engineering

True stories of the workplace experiences of women engineers and reflections on recent developments.

Wednesday, February 14, 2024

It's not just Engineering (the drowning dog story)

Wednesday, July 6, 2022

Whatever it is, it's more Important if Men have it

by Denise Wilson, June 6, 2022

I read an interesting paper recently (Uhlmann and Cohen, 2005) about how both men and women in three different experiments/studies did not identify men or women by their strengths and weaknesses. That's good news, right! Yay!

I should have stopped reading right then and there.

But I read on. And discovered that in making hiring decisions, people tend to define the credentials for a job by the characteristics that the desired gender just happens to have. In engineering, that means, the desired credentials for an engineering job align with the skills and expertise that male applicants have. And if, as a woman, you don't happen to have those skills, credentials, or expertise, well... you are out of luck (and likely to remain unemployed for longer than your male peers).

The experiment involved 73 undergraduates (both. male and female) who were provided written descriptions of applicants for the job of police chief (a traditionally male dominated position). The written descriptions were of (a) an applicant who was very streetwise (tough, got along with coworkers) but not formally educated and (b) an application who was highly educated but not particularly streetwise.

The good news is that when those in the study evaluated the written descriptions of applicants, they rated streetwise and educated characteristics similarly whether they believed the applicant to be male or female. In other words, they demonstrated no stereotypes regarding which gender has better streetwise or educated characteristics.

While the lack of stereotyping was reassuring, the participants (evaluators) in the study nevertheless discriminated against women in hiring recommendations for the police chief position When given the exact same description of an applicant, evaluators rated the job applicant less positively when the evaluator thought the applicant was a woman than when they thought the applicant was a man.

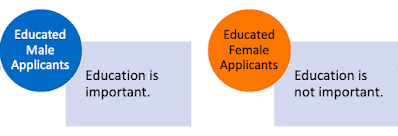

And, when evaluators thought an educated applicant was a woman, they reported that educated characteristics were less important while when they thought an applicant was a man (with the same written description of experience and characteristics), they viewed educated characteristics as more important. Even when evaluators were assessing stereotypical female characteristics like being family oriented, these characteristics were viewed as more important for police chief when the male applicant possessed them compared to when the male applicant did not.

The bottom line... when men have it, it's viewed as more important to the position and ultimately to the hiring decision. When only women have it, it can be less important to the position and ultimately to the hiring decision. Good news for women who just happen to have the same characteristics as the men in the applicant pool, but where does that leave the rest of the women searching for jobs in a male dominated field like engineering?

While this seems to be dismal news for women seeking work in male-dominated fields, the authors of this research didn't leave us in such a dismal place. In another experiment, they recruited local community members and split them into two groups: (1) those who entered the hiring evaluation process with no formal criteria for evaluating applications; and (2) those who entered the process with established formal criteria in hand. And for the latter group, gender bias and discrimination disappeared.

This type of bias has a name -- Constructed Criteria Bias.

More importantly, it has a solution.

In field which are dominated by a single gender, this kind of bias calls for organizations of all types -- government, academic, and private sector -- to carefully craft hiring criteria and rubrics long before taking a look at any applicants, male, female, or otherwise.

Monday, June 6, 2022

The Reality of Graduate School

Graduate school involves many good things. But unfortunately, it tends to provide less of those good things for women in engineering doctoral programs.

Many of the important outcomes for graduate school relate to how you build knowledge for yourself and for your academic area. It is an opportunity to become an expert in a particular field. In engineering, graduate school is a chance to become a meaningful contributor to the knowledge economy. It's a place to pursue knowledge for the sake of knowledge. It's a time to dive deep into a specialized topic of research and discover something new...to invent and innovate. It's a unique time to immerse oneself without interruption in underlying scientific principles and devise new ways to apply these principles to the betterment of society.

But graduate school should be about much more than developing technical expertise. Graduate school can also be a time of building community, through networking among peers and among a wide range of professionals, from professors to industry leaders. It should be a time to build confidence and conviction in pursuing the career that lies ahead, whether it be in academia, in the corporate sector, or in the non-profit world. Graduate school should be a time of not only learning and skill building but also a time of finding one's place in the vast landscape of science, technology, and engineering.

Regardless of how graduate school varies by individual experience, once the PhD is stamped next to a person's name, the individual who earned it should feel nothing less than welcome, invited, appreciated, and capable in their respective research community.

Unfortunately, a recent study of 913 doctoral students across 112 universities and 23 engineering disciplines suggests that for too many women, this is not at all what happens for them as they enter and progress through their graduate programs in engineering. 16% of non-White women said that they had been treated unfairly by their primary research advisor and 20% reported unfair treatment from graduate student peers. These numbers rose to 20% and 22% for women from marginalized race or ethnicity, including American Indian or Alaska Native; Black or African American; Hispanic; Latino/Latina/Latinx or Spanish origin; Middle Eastern or North African; Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; or another race or ethnicity that was not Asian or White.

When these graduate student women were asked more specifically about the negative experiences that they had been exposed to during their graduate programs, many reported that their ideas were not given a fair shake at the research table. 43% of non-White women overall, and 20% of women from marginalized groups, said that it was quite common to see a female graduate student present an idea and get no response while a male student presenting the same idea would be acknowledged. 36% of non-White women and 30% of women from marginalized groups also reported that their peers attempted to exert authority over them because of their gender. In terms of positive experiences in their graduate programs, less than a quarter of all non-White women thought that their research advisor treated students of different race and ethnicity the same.

Unfair treatment of graduate students can increase feelings of isolation, decrease sense of belonging, and impair motivation at a time in professional and intellectual growth where these are most needed to empower the student to reach their full potential. Psychologically, loss of belonging can reduce the likelihood that students will seek help for both intellectual and emotional concerns, thereby exacerbating the ongoing mental health crisis among graduate students.

Tuesday, May 3, 2022

What's a Guy to Do When a Woman Is Being Harassed?

The following vignette is based on true accounts of what happens when women are exposed to repeated romantic or sexual overtures in the workplace. It also incorporates proven bystander intervention strategies that don't require direct confrontation of the perpetrator but can nevertheless be very effective at reducing or eliminating the offensive and harassing behavior.

I’m an engineer. I’ve been out of school for seven

years and I love my job. I’ve had no trouble moving up the ladder at work and

am headed toward a senior engineering position after I finish up my current

project. I like my boss. I like the hours. I even like the traveling. For the most part, I like and respect all of my coworkers...except Mark.

Mark is at least a decade older than me and much older than the new engineers that roll in the door every summer, fresh graduates eager to make a good impression. The guys have to put up with his raunchy jokes and the porn pic of the day that he insists on showing us when we need to stop by his cubicle. It’s irritating. But for Molly, it's worse. She has to put up with Mark's repeated overtures. I have overheard Mark pressuring Molly to go out with him about once every week, and I am sure what I overheard is only the tip of the iceberg. But, I had a job to do and it kept me busy. So, for the most part, I put up with Mark and let Molly deal with Mark's repeated and unwanted overtures.

When the time came for another round of sexual

harassment training, I was ticked. I was in the middle of a key turning point

in my current project and I didn’t have time for another round of perfunctory

PowerPoint. I was even more aggravated by the fact that all this PowerPoint

wasn’t doing a single thing to stop Mark from his obnoxious behavior. As I sat down for the training, I was fuming. What a

waste.

But this year, the training folks had added another module to the sexual harassment training program, focused on bystander intervention. An hour into the new module, I was practicing the five D’s (delay, delegate, distract, document, direct) - and feeling totally uncomfortable with direct and distract. I just didn’t feel confident about intervening in the moment. But there was something there with the delay and document skills. I could definitely see myself doing that. I thought about Molly and felt guilty that I had just left the problem on her plate because I thought myself to be too busy and important to deal with what was "her problem."

I had walked into the training frustrated and annoyed. I walked out feeling badly about my own inaction but determined to do something about the Mark and Molly situation.

I didn't have to wait long for my opportunity. The next day, I came across Mark doing his thing with Molly. As I suspected, I chickened out on confronting the situation directly, but later, after Mark had gone home for the day, I stopped by Molly’s cube and asked her about how she felt about the encounter Molly. At first, she said it was no big deal, but I chatted a little while longer and she started to open up. She used the word creepy over and over again.

In the following months, I talked to Molly a lot, learning more and more about what she had to put up with Mark. I still couldn't bring myself to confront Mark, but I started taking lots of notes in my conversations with Molly and with her permission, I did what I should have done months, if not years, before. I gathered my notes and sat down with my manager. I started the meeting by telling him flat out that Molly could be contributing a lot more to the organization if we just addressed the Mark part of her equation. Given how desperate we were for more engineering person-power, I had hoped that would pique my manager's interest - and it did.

The conversation went on for over an hour. We strategized how to address the behavior without alienating Mark or Molly. In the end, however, we accepted that despite our best efforts, Mark might have to leave our group, if not the organization. My manager followed up by talking to Mark. When Mark jumped on the defensive or tried to minimize what he was doing to Molly, my manager was able to insert into the exchange many of the specifics I had given him. Mark stayed defensive and angry after that meeting. After a couple of months of an angry and sulky version of Mark, we were told that Mark had left the company and we needed to find a way to fill his shoes.

Fill his shoes. Yeah. Right. No thank you.

What surprised me the most was Molly. She had been doing okay in her job before Mark left, but still, I had often felt my patience running thin with some of her mistakes, particularly the technical ones. I had thought she would work through it as she settled into her first job, but I was starting to wonder if she had what it takes to be an engineer. After Mark left, though, her performance shot way up. She was already easy to work with, but without the harassment hanging over her head, her technical skills quickly ramped up - so much so that I quickly forgot why I was ever impatient with her.

When someone is harassed in the workplace they cannot produce, contribute, or work up to their potential. Working to eliminate the harassment is well within the reach of coworkers and does not have to involve direct confrontation to the harasser. Want to know more about bystander intervention? Check out these resources:

- VanAntwerp, Jennifer, and Denise Wilson. Sex, Gender, and Engineering: Harassment at Work and In School. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2022. See Chapter 11, "Solutions," pp. 188-224.

- The 5 D's of Bystander Intervention (Right to Be organization)

Harassing behavior can push people to leave their jobs and even their careers. It creates workplaces that are less productive and less welcoming.But of course, the climate of a workplace depends on much more than harassment. Would you like to participate in the ongoing research study about the workplace climate for engineers and computer scientists? You can help us understand what the workplace feels like to individuals - and you can help illuminate how to change things for the better for everyone. (This research is sponsored by the University of Washington and Calvin University.)

The survey must be completed before you close your browser.

Sunday, April 10, 2022

Dressing for Success as an Engineer

On the first day at my new job with a civil engineering firm, I felt more than a little bit anxious. I wanted to make a good first impression. I had spent much of the night before agonizing over my wardrobe. I knew from my interview that office wear was generally business casual. But what did that mean for me?

There were times when I really wished I could be a man. Engineering work uniform? Cotton dress slacks, long-sleeve dress shirt. Add a tie if meeting with a client. Replace loafers with sturdier work boots on days with a site visit. In fact, I knew one guy I went to school with who literally had a closet lined up with 8 of these identical outfits. Getting dressed in the morning was not a mental chore at all.

But there was no easy equivalent to this outfit for me, and I frankly didn’t want to adopt his model of dress anyway – the style was not at all flattering to my body shape. Plus, the slacks and dress shirt somehow managed to look far more casual on a woman than a man. I wanted to be taken seriously as a professional, so too casual was not an option. So, I did my best to choose slacks and a blouse that were cut for a woman’s figure, but not too fussy or delicate. But I still felt anxious about my choices. I couldn't shake the feeling that I wasn't hitting the mark.

Unfortunately, I didn’t find choosing what to wear any easier after a few weeks at work. There were no other women engineers in my workgroup from whom I could even take a hint. The administrative assistants were mostly female, but their short, tight pencil skirts with silky blouses and spike heels didn’t seem like a good choice for the variety of tasks in my job. And frankly, I didn’t want to attend a meeting again where I would be mistaken for the secretary coming to take the meeting minutes, like had happened to me the first week. The manager who had done so was certainly apologetic…but he also wouldn’t meet my eye or directly address me during that meeting, I think out of embarrassment. Which certainly didn’t serve my career very well.

I experimented with slightly different clothing at first, trying to figure out what would work. But just as I was starting to feel like I was narrowing in on a style, I started picking up on office chatter that sent my anxiety soaring again.

First it was the two guys chatting in the cubicle across from me. “Yeah, Julie was the only one who spent enough time on that part of the project to really know what the hold-up could be now. I would sure like to pick her brain now. But, well, it couldn’t be helped. I mean, we really couldn’t keep her on…”

I knew Julie was the engineer who I had replaced, but I hadn’t realized she had been fired. Not the sort of news that instilled peace and calm in me in the new job...

Then it was the awkward moment in the team meeting, when we were trying to figure out how to mollify a client who was being particularly difficult. My colleague Jack casually tossed out, “Well, too bad we don’t have Julie anymore. Here is a situation where we really could have made use of those low-cut blouses she liked to wear.” Some of the other guys chuckled, and some glanced my way and looked a bit uncomfortable. But no more was said, and the meeting moved on.

The final blow was when I had my regular one-on-one with my supervisor. He made some comment about transition challenges in the project I was taking over from Julie. In what I assumed was an unguarded moment, he explained to me that they hadn’t had the usual time to go through exit procedures and project transfer because the split had been awkward.

“Julie was a good engineer, but we had to let her go because she just wasn’t fitting in. I mean, she wore these shirts that were just unprofessional. Some had these wild, bright patterns and I just didn’t know if our clients would be confident in her ability as an engineer. I had talked to her about it, but she didn’t really change how she dressed. And then some of her blouses were a bit too sheer. They were really distracting to the guys….” He paused and cleared his throat, as if realizing he had overshared. He cleared his throat awkwardly. “Well, you know what I mean. Of course, it wasn’t just about that. We just needed someone who could be more of a team player. And we’re so glad to have you here. Your work is solid, and we are so glad to have a woman engineer in the group. I mean, I know how important that is. I keep hiring women, but we have really had trouble keeping them here.” And then he quickly changed the subject.

Well, if I had been nervous about my work wardrobe before, now I was petrified. It seemed that if I missed the mark, I was in danger of being fired. Maybe it was time to go get those khaki slacks after all and forget about bringing my personality to work with me?

Wednesday, February 16, 2022

Our Words Do Matter

by Jennifer VanAntwerp, February 16, 2022

Women and their work are valued less in our society. This cultural bias can be measured in the very way that we use, and change our use of, language in describing the types of work we do in STEM.

It's no secret that pushing STEM (science, engineering, technology, and math) participation is a hot topic in the U.S. What might be less well-recognized is that not all STEM is considered to be equal – and this has real (and negative) consequences for women.

New research by psychologists Alysson Light, Tessa

Benson-Greenwald, and Amanda Diekman has revealed biases in

how we describe, perceive, and value the various STEM fields. Study

participants from all walks of life were presented with brief (and true) descriptions

of different STEM fields (including some physical sciences, some social

sciences, and some engineering). However, none of the descriptions were identified

by name. In addition, a gender composition for the unnamed field was provided –

but participants were randomly assigned to groups that were either told the

field just described included mostly males or told that that same field was majority

female. They were then asked to categorize each field as a “soft science”

or a “hard science.”

It turned out that the exact same description was significantly

more likely to be labeled by participants as a soft science if the respondent

believed the field to include more women than men. The opposite was true for

majority men and the hard science label – regardless of which discipline was

actually being described. In other words, there is a strong cultural bias that

women do something called soft science and men do something called hard

science.

Wikipedia tells us that "hard and soft science are colloquial terms used to compare

scientific fields on the bases of perceived methodological rigor, exactitude,

and objectivity." This naturally sets up soft sciences as being inferior

to hard sciences; it implies a societal judgement that soft science is pseudoscience

– less difficult, less reliable, less valuable. In fact, additional results

from this same research study make it quite clear how these perceived soft/hard

sciences differences are valued. When Light and colleagues asked participants to evaluate the value

of a discipline based only on its label as a hard or soft science, the soft

sciences lost on every single measure. As the study authors conclude, “the

general category of soft sciences is perceived as less rigorous, less

trustworthy, and less worthy of funding than hard sciences.”

But why does the lower valuation of soft sciences matter to

engineers? Clearly engineering disciplines are firmly in the hard sciences

camp, right? Well, it matters because at a subconscious level, women are associated

with these less respected and less valued fields of work. The spillover from

this is that at a subconscious level, all women suffer a blow to their

credibility, status, and contribution as members of STEM fields – including those

women in engineering.

So perhaps it is no surprise, then, that women engineers are

2.9 times as likely as

men engineers to report “I have to repeatedly prove myself to get the same

level of respect and recognition as my colleagues” and 2.8 times more likely than

men to agree that “After moving from an engineering role to a project

management/business role, people assume I do not have technical skill.” (And unfortunately, research also has

demonstrated that engineers place more value on technical skills than

communication, planning, managerial, or similar essential skills.) No surprise

that women working in STEM are less likely

than men to have their ideas endorsed by leadership or green-lighted for development.

They are judged, whether explicitly or implicitly, to be less of a “fit” for more “rigorous” or “hard science” work. And in some ways, it might not matter even if women do manage to get assigned to these more valued job assignments. Simply because more women are doing a job, it can come to be less valued. Yet one more example of women engineers facing the “damned if you do; damned if you don’t” barrier.

Have you had a similar experience to Our Words do Matter or would you like to share a story, concern, or experience that relates to what you have just read? Click here to share (all responses are private and kept confidential). |

|

|

Jennifer J. VanAntwerp is a professor of

chemical engineering at Calvin University in Grand Rapids, Michigan. She

researches how engineers learn, work, and thrive, beginning in college and

extending throughout their professional careers. |

Wednesday, November 10, 2021

Gender Bias in Student Evaluations of Teaching

Student evaluations of teaching (SET) were originally designed to be formative by providing valuable input to instructors in higher education. When used as a tool for improving teaching, student responses to close-ended and short-answer answer questions on SETs can provide helpful feedback to instructors as well as those who mentor or otherwise work with instructors on professional development.

Since their initial introduction, however, SET have continued to shift from formative to summative. In many institutions, the ratings provide by students on a just a small subset of items far overshadow the short answers and other items that in total, provide a more comprehensive picture of college teaching. The numbers within this subset of ratings are often used in key decisions for promotion , tenure, hiring, and firing.

Using this shorter list of SET numbers is convenient and quick. Unfortunately, there is plenty of evidence that these ratings are biased and are not consistent or adequate measures of student learning (a short review of the literature can be found here). Gender bias, where female instructors consistently receive lower ratings than their male peers for the same courses or for different sections within the same course, is especially well documented. Such bias generates concern about how SET ratings are used by higher education institutions to evaluate women instructors and how these ratings impact the future morale and effectiveness of the women who read them and take them to heart.

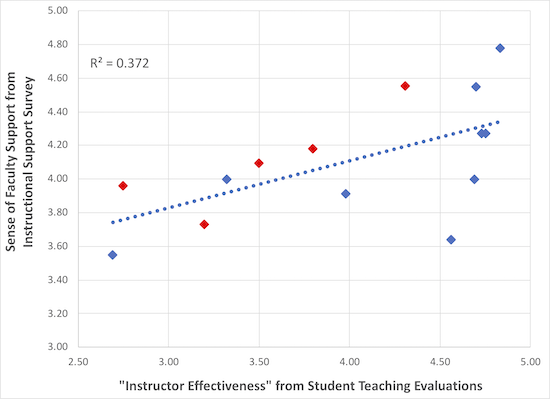

Recently, our research team compared student perceptions of how well faculty supported them in their courses with how those same students rated those faculty on student evaluations of teaching in engineering courses at one large public university. We compared a pair of median scores: Instructor Effectiveness in the Course (SET) and Students' Sense of Faculty Support (our survey).

Instructor Effectiveness was measured using the median score from one item on the university SET form: "The instructor's effectiveness in teaching the subject matter was:" Students had the option of selecting Excellent (5), Very Good (4), Good (3), Fair (2), Poor (1).

Students' Sense of Faculty Support was measured in a research-based survey that was not affiliated with the university's educational assessment office. Faculty support contained eleven items that had been validated in multiple previous studies in higher education and had a high internal consistency (reliability) of 0.92:

- The professor in this class is willing to spend time outside of class to discuss issues that are of interest and importance to me.

- The professor in this class is available when I need help.

- The professor in this class is interested in helping me learn.

- The professor in this class cares about how much I learn.

- The professor in this class treats me with respect.

- The professor has clearly explained course goals and requirements.

- The professor teaches in an organized way

- The professor often uses real-world examples or illustrations to explain difficult points.

- The professor often stays after class to answer questions.

- The professor often stops to ask questions during class.

- The professor is often funny or interesting.

All of the above items were rated on a scale from Strongly Agree (5) to Strongly Disagree (1).

When we compared SET Instructor Effectiveness to Students' Sense of Faculty Support, we found that when asked a general question about instructor effectiveness, students exhibited negative bias toward women relative to more specific (and objective) questions about faculty support behaviors. Students completed both the instructional support surveys (that contained the Faculty Support items described previously) and SET in the last 2-3 weeks of the term associated with the course being evaluated. Four of the five female instructors (80%) in the study received higher Faculty Support ratings than their SET ratings would suggest while only three of the nine (33%) of the male instructors did so (female instructors are shown in red; male instructors in blue):

Have you had a similar experience to Our Words do Matter or would you like to share a story, concern, or experience that relates to what you have just read? Click here to share (all responses are private and kept confidential). |

It's not just Engineering (the drowning dog story)

I regularly head down to a small marina near my home where I can get a waterfront property experience without paying ridiculous property tax...

-

I regularly head down to a small marina near my home where I can get a waterfront property experience without paying ridiculous property tax...

-

A Story from the Engineering Workplace There is a hidden tax for women in the engineering workplace...extra tasks or an extra mental load ...

-

Research has shown that engineers, on average, have lower empathy than those working in a wide range of other disciplines. Unfortunately, l...